My New Orleans - April 21, 2022

Healthy Festival Eats and New Orleans as You Have Never Experienced It

Vue Orleans is the main attraction during a New Orleans food festival this month as a new dazzling showcase of NOLA culture.

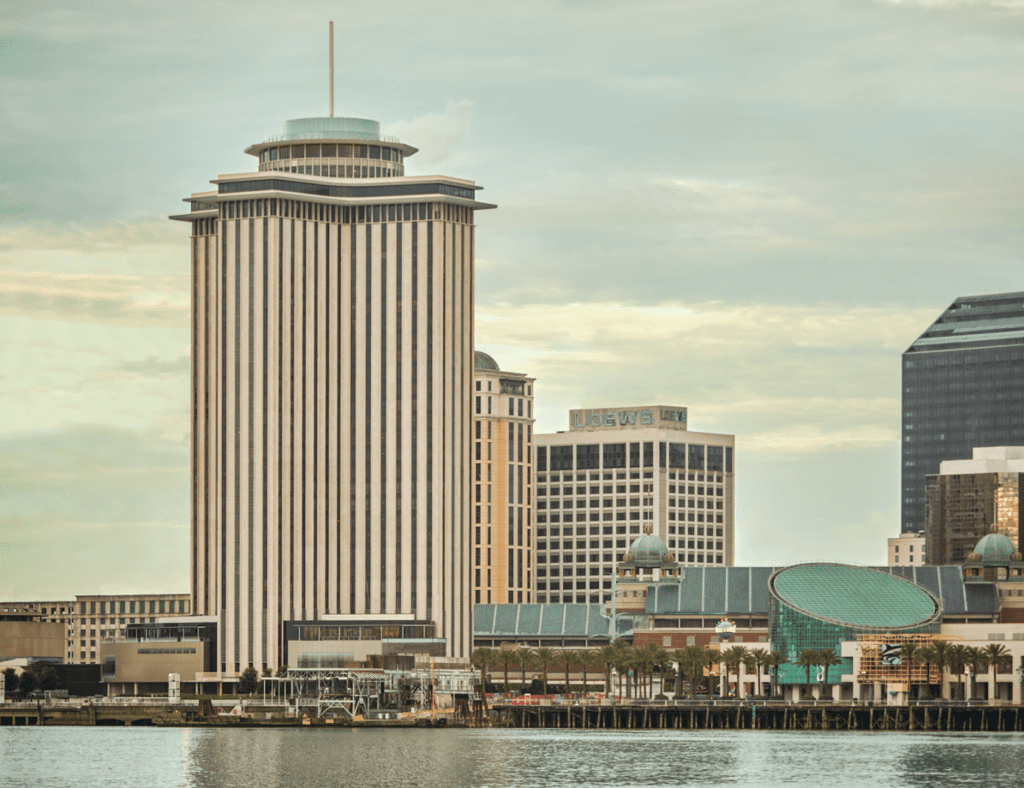

View PostIn a city well-known for its 19th-century architecture, this soaring modernist skyscraper remains one of the most recognizable in New Orleans’ skyline. Its prominent location, where Canal Street meets the Mississippi River, is also no coincidence. When it was designed as the International Trade Mart and built in 1967, the prime riverfront spot was seen as the crossroads of the world, and the building’s compass-shaped design reflected New Orleans’ role in global trade.

After sitting vacant for years, and avoiding the looming threat of demolition, the tower recently completed an extensive multi-year renovation for its new life as the Four Seasons Hotel and Private Residences, which opened its doors in the summer of 2021. Today, the building gleams once again in the skyline as a prominent new landmark to the growing industry of this age: the hospitality and tourism sector.

The 33-story tower was less than 50 years old when it, and the adjacent Spanish Plaza, were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2014 for exceptional architectural significance.

The structure was built between 1964 and 1967 with the hope of promoting international trade at the nearby Port of New Orleans. The skyscraper was designed by Edward Durell Stone, an Arkansas-born architect who achieved international fame and influence. Some of his other well-known designs include the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, India, and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

Stone was a pioneer of the New Formalist architectural style, which rejected the strict modernist aesthetic of the mid-20th century and instead sought to combine new building technologies with classical precedents. New Formalist buildings use classical proportion and scale to give a sense of monumentality, and often have symmetrical facades and stylized classical details including columns, arches and entablatures. Building surfaces were typically smooth, using rich materials like marble or travertine to convey luxury instead of applied ornamentation.

The International Trade Mart building is an excellent example of the New Formalist style popular during the 1960s. “Stone, who was a modern classicist, asserts here a mid-20th century focus on classical symmetry and order in the building’s rhythm of vertical and horizontal elements,” according to the building’s listing in the National Register, prepared by Karen Kingsley. “In a modern way, the International Trade Mart references the city’s plethora of historic classical architecture.”

Just like a classical column, the soaring skyscraper’s design has a base, shaft and capital. At its two-story base, a dark glass lobby with an overhanging canopy gives the rest of the building a free-floating effect. Its interior has luxurious finishes, with white Italian marble walls and floors, and Verde Antique Italian marble-clad columns soaring through the space. The building’s vertical “shaft” then rises for 28 stories above the base, covered in vertical bands of windows and concrete aggregate panels that give the visual effect of a fluted column when viewed from a distance. Above, the building’s “capital” includes two more overhanging canopies, and the structure is topped with a cylindrical “cap” which once contained a revolving cocktail lounge.

Stone designed the building with an unusual cruciform floor plan. Its four wings point in each cardinal direction, as a symbolic reference to international trade and New Orleans’ reach to the four corners of the world.

Original marble finishes now shine inside the restored lobby much as they did when the building first opened in 1968. Today, locals and visitors rub elbows at the Chandelier Bar, which sits in the middle of the space beneath the namesake chandelier that acts as the lobby’s sparkling focal point. Image courtesy of Four Seasons Hotel New Orleans. “Before” image by Davis Allen.

The International Trade Mart teemed with activity during Louisiana’s oil boom of the 1970s and early 1980s, when it played host to noteworthy guests, international dignitaries and sitting presidents of the United States. But along with the oil bust of the mid-1980s, activity in the building also slowly dried up as the offices, law firms and foreign consulates inside began to move out. The last remaining tenants were vacated in 2009, leaving the tower vacant for years to come. The City of New Orleans then bought out the building’s lease from the World Trade Center organization in 2012, giving it full operational control over the site’s potential redevelopment plans.

The city solicited proposals for redevelopment of the site without placing any limitations on whether the building would be demolished or renovated. When one of the proposals called for the building’s demolition, it struck a nerve with many New Orleanians. Preservationists sprang into action.

Yard signs popped up across the city in support of saving the skyscraper. The building landed in the No. 1 spot on the Louisiana Landmarks Society’s 2013 “New Orleans Nine,” an annual list of historic buildings in the city threatened by demolition. Advocacy efforts by local organizations, including the Preservation Resource Center, helped to fill public meetings at City Hall that summer, where residents voiced their opinions overwhelmingly in support of saving the skyscraper and keeping tons of building material out of the landfill.

“Preservation of the World Trade Center building is also good economic development,” said a statement from the PRC’s Board of Directors in 2013. “Our visitors love New Orleans for its unique sense of place. The World Trade Center building certainly has a role to play in that. It should remain and not sit vacant any longer.”

In echoes of efforts during the 1990s to prevent the demolition of the nearby Curtis and Davis-designed Rivergate, New Orleanians showed up to defend another noteworthy modernist structure and fight for its preservation. While local advocates were ultimately unsuccessful in saving the Rivergate (Harrah’s Casino sits on that site today), the fight to save the International Trade Mart ended with a preservation success story.

The message was received by the city loud and clear in 2013, and a proposal to redevelop the site into a hotel and residential units was chosen instead. Although that initial redevelopment plan fell through, the city’s next call for redevelopment proposals only considered plans to rehabilitate the existing building instead of demolishing it — thanks to the previous public input, advocacy effort by historic preservation organizations, including the PRC, and the eligibility for historic rehabilitation tax credits following the tower’s addition to the National Register in 2014.

In 2015, the city chose a proposal by developers Carpenter & Co. and Woodward Interests to transform the dormant tower into a Four Seasons hotel, private residences and a cultural attraction.

The building’s once-cavernous lobby is now partitioned into cozier, intimate nooks with potted tropical plants and louvered screens — an architectural reference to the exterior louvers on the building’s windows. “Before” image by Davis Allen. “After” image courtesy of Four Seasons Hotel New Orleans.

After years of planning and negotiations, the project broke ground in 2018 and the tower’s multi-year rehabilitation ensued. When the Four Seasons Hotel and Private Residences opened its doors to its first guests in August 2021, the long-anticipated transformation of the building took on a new importance as the city hoped to recover from the pandemic’s effects. Although Hurricane Ida took aim at New Orleans just weeks after the Four Seasons’ opening, business — and excitement for the new property — began to pick back up shortly afterwards as the city rebounded from the storm.

“When we first opened, so many locals were coming into the building just to see it brought back to life and to see what it had become, and that was really exciting for us,” said General Manager Mali Carow. “Once we opened our doors, it felt like New Orleans also opened its doors to us, and there was this energy that came back into the hotel.”

The site’s public spaces have already become new hot spots for locals and guests. In the lobby, New Orleanians rub elbows with international visitors at the Chandelier Bar, where the original white marble finishes and green marble columns shine much as they did when the building first opened in 1968. A curved bar now sits in the middle of the space beneath that namesake chandelier that acts as the lobby’s sparkling focal point. The once-cavernous room is now partitioned into cozier, intimate spaces with potted tropical plants and louvered screens — an architectural reference to the exterior louvers on the building’s windows — dividing the large, open space. The lobby, as well as most of the hotel’s other interior spaces and guest rooms, were designed by Bill Rooney Studio.

“We’ve kept a lot of the architectural details of the building and what made it beautiful and unique, and we were able to modernize elements of it as well,” Carow said.

Massachusetts-based architecture firm CambridgeSeven oversaw the building’s transformation as the project’s lead architect and collaborated with local firms Woodward Design+Build and Trapolin-Peer Architects to renovate the building. The construction was led by a joint venture between Woodward and AECOM Tishman.

The historic tower was restored to house the hotel’s lobby, 341 hotel rooms and suites, and 92 private residences above. A new, curving five-story addition was built alongside the tower to house the hotel’s new pool deck, ballrooms, fitness center, spa and a restaurant space.

A small addition to the building’s roof added a 34th story to accommodate an observation deck and café for a new cultural attraction, named “Vue Orleans,” which opened earlier this year. There, inside the space that once held the building’s rotating bar, visitors can learn about New Orleans’ culture and history through interactive museum exhibits and take in a breathtaking 360-degree view of the city. Instead of the quarter-fed binoculars of yore, visitors can move digital viewfinders around the scenery and use touch screens to tap on landmarks or neighborhoods in the distance to learn more about their history.

Four Seasons also partnered with local award-winning chefs to bring two popular new restaurants to the hotel. On the fifth floor, Chef Donald Link’s restaurant, Chemin à la Mer, has panoramic views of the Mississippi River and a menu with French and Louisiana flavors, steaks and an oyster bar. On the first floor is Chef Alon Shaya’s Miss River, which the restaurant’s website calls Shaya’s “love letter to Louisiana,” highlighting local ingredients and bold flavors. That space was designed by London-based Alexander Waterworth Interiors with curvilinear Streamline Moderne-inspired details that give a nautical nod to the Mississippi River.

The building’s revitalization has brought new economic opportunities to the city at a critical time during its recovery from the pandemic. In addition to the construction jobs created during its multi-year renovation, the new destination now has a large employee base, including newcomers to the hospitality sector as well as seasoned industry veterans. “We have a team of about 500 here at the hotel, and it’s been exciting to bring them into the Four Seasons family,” Carow said. “Everyone has this pride and this love for their city that they share with their guests.”

Today, the once-vacant site is again bustling with activity as locals, visitors, residents and employees come and go from the Four Seasons. As other nearby civic projects work to re-activate the riverfront — including the construction of the nearby Canal Street Ferry Terminal — it seems that the city’s decades-long dream of re-enlivening the riverfront is finally coming to fruition.

1: Chef Donald Link’s restaurant Chemin à la Mer is located on the fifth floor in a new wing built during the site’s recent redevelopment. 2: The interior design of Chef Alon Shaya’s restaurant Miss River, located on the building’s first floor, features curvilinear Streamline Moderne-inspired details that give a nautical nod to the Mississippi River. Images courtesy of Four Seasons Hotel New Orleans.

My New Orleans - April 21, 2022

Vue Orleans is the main attraction during a New Orleans food festival this month as a new dazzling showcase of NOLA culture.

View PostThe Architect's Newspaper - June 22,2021

CambridgeSeven's dramatic renovation of this historic New Orleans tower is about to be unveiled.

View PostThe Times Picayune - Nov. 11, 2020

A New Orleans landmark skyscraper is set for a spring unveiling as a top-of-the-line Four Seasons Hotel and Private Residences.

View Post