What the Four Seasons’ opening means to New Orleans: a key milestone in its recovery

The Times Picayune - Nov. 11, 2020

A decade after it was vacated and taken over by New Orleans government, the landmark skyscraper where Canal Street meets the Mississippi River is set for a spring unveiling as a top-of-the-line Four Seasons Hotel and Private Residences.

The $530 million renovation of the former World Trade Center, which will have taken three years to complete after decades of false starts, was targeted by former Mayor Mitch Landrieu as one of the city’s most significant developments after Hurricane Katrina. Transforming the building from an unoccupied shell to a model of chic opulence, it was argued, would be a key milestone in New Orleans’ progress and continued recovery from the 2005 storm.

Now, with the coronavirus pandemic straining New Orleans’ hospitality sector to its breaking point, the long-delayed launch of a new hotel at the very top end of the market has taken on added weight for the city.

Mali Carow, a Four Seasons veteran who was picked last year to be the hotel’s general manager, said the delays have given her more time to settle into New Orleans and to think about the place she hopes the Four Seasons will occupy in the city’s hospitality ecosystem once normalcy returns.

“What I’m hoping is that once we get through this challenging time, we’ll be a place that all of New Orleans wants to come and have a celebration,” she said. “New Orleans likes to celebrate, and this has been a tough year.”

The World Trade Center was designed by Edward Durrell Stone, a famed mid-20th Century architect who also designed the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington. It was completed in 1967 and was originally known as the International Trade Mart.

Once a premier New Orleans office location, it was hit hard by the 1980s oil bust and by the late 1990s was being considered for redevelopment. Those plans foundered over the course of a decade, and in 2010 City Hall considered demolishing the building.

By 2014, the Landrieu administration had received 11 proposals from developers seeking to transform the site. The Four Season consortium was selected in 2015. Lawsuits held up construction until 2017.

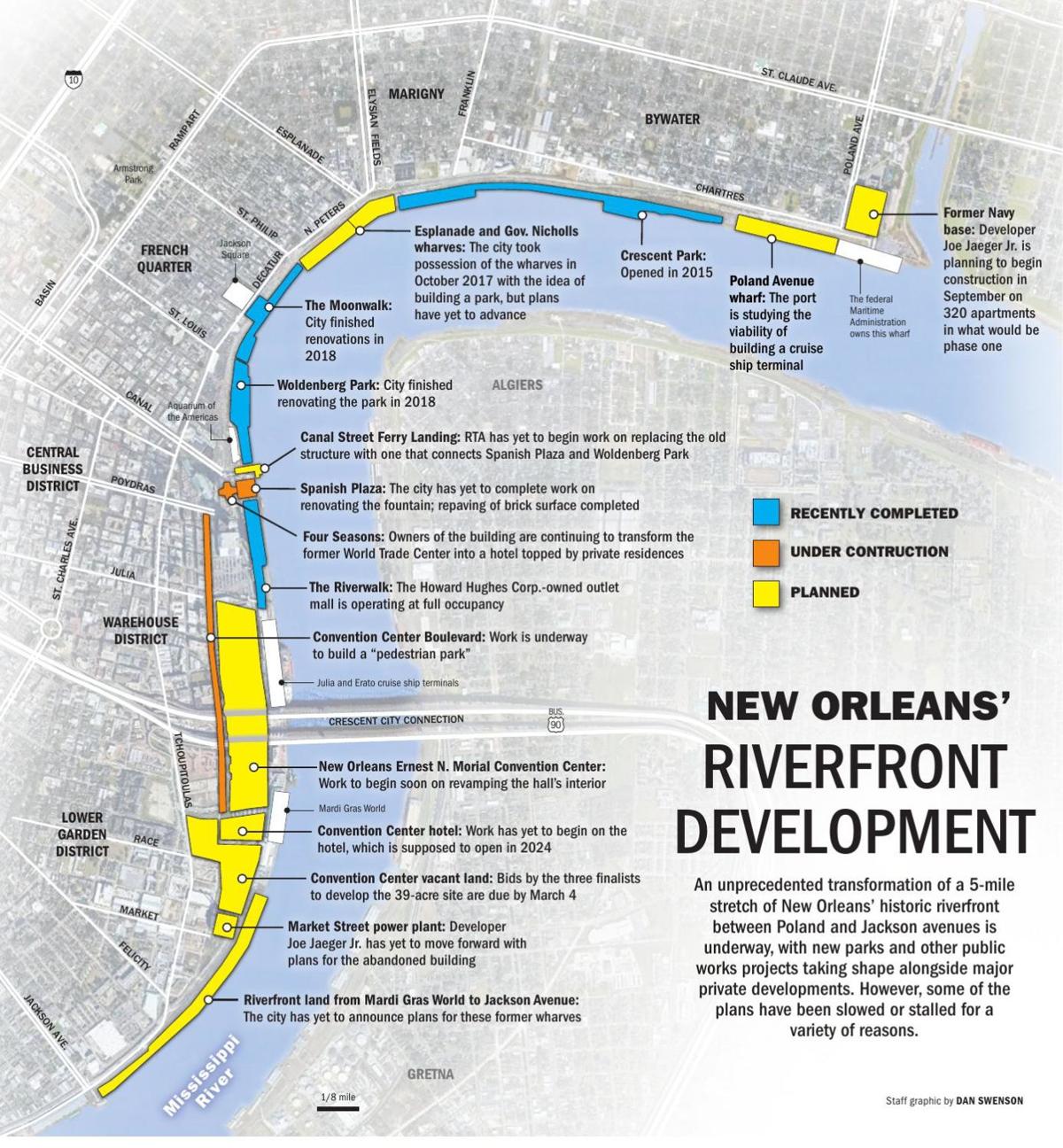

The development is part of the larger urban waterfront revival plan aimed at breathing new economic life into New Orleans downtown area, similar to conversions of wharf areas in cities such as Nashville, Tennessee, and Baltimore into bustling hubs. Spanish Plaza, which is undergoing a $7.5 million facelift of its own, connects to the riverfront side of the new hotel.

The success of the Four Seasons will, of course, require a revival of the city’s crippled hospitality industry, which has virtually ceased since the coronavirus shutdowns began in March.

But local officials hope the luxury appeal of the Four Seasons will quickly draw tourists once restrictions are lifted. Stephen Perry, CEO of the city’s tourism marketing organization, New Orleans & Co., said the affluent end of the market typically is the most robust.

“Our research shows that the traveler sentiment is best among those in the luxury market,” said Perry, adding that luxury travel was seeing high single-digit annual growth before the pandemic.

Market research firm Allied Market Research forecast last year that culinary-driven luxury destinations such as New Orleans would do especially well, growing through 2026 at a clip of almost 10% a year.

Still, Perry adds, a property such as the Four Seasons depends on the return of gatherings like company board meetings and high-end conferences for surgeons and the like — travel that has all but disappeared due to the pandemic.

“I think you’re going to see us making some incremental gains into the first two quarters next year, but nothing that resembles 2019 levels until the point at which we get a vaccine and it is administered to large segments of the U.S. population,” Perry said.

The Four Seasons owners are banking on that happening in time to open in the spring.

On a recent tour of the building, it took some imagination to visualize the promised luxury amid the clamor of rivet busters and heavy drills, with 650 construction workers still tromping through the site’s 744,000 square feet.

Scott Buhler, one of the project managers, said the building will finally be closed in by the end of the year and the landscaping and sidewalk finishing will begin.

Approaching the entrance, there is the outline of a sweeping circular driveway. It will deliver hotel guests to a foyer that, Carow assures, “will have an amazing 16-foot chandelier, which is still being designed, and a bar literally as you step into the hotel. It’ll be an incredible social thoroughfare.”

To the left of the entrance, the bar will open out onto 7,500 square feet of garden space that can be tented and air-conditioned for receptions and events.

Owners of the 92 residences will veer right to their private elevators, which will raise them more than 200 feet to condominiums starting on the 19th floor and beyond to the penthouses between the 29th and 33rd floors. The latter are being marketed at $7 million and $10 million, said David Seerman, sales director for Carpenter & Co., the master developer and partner in the project with Paul Flower’s Woodward Interests.

The lobby bar, which has yet to be named, will be operated by Pomegranate Hospitality, the firm established three years ago by Israeli-born chef Alon Shaya and his wife, Emily. Also, the Four Seasons recently announced, Shaya will run a yet-to-be-named ground-floor restaurant that he says will feature a Louisiana-influenced cosmopolitan menu.

Still being mulled are the naming of the Shaya-run restaurant and bar; picking an executive chef, naming and theming the fifth-floor restaurant; and naming the ballrooms on the third floor and the event space in the iconic two-story cupola at the top of the tower.

“It’s really important to me that when this property opens, it’s going to be a New Orleans property,” Carow said. A committee that includes “everyone,” from the owners and Four Seasons management to local culture bearers, is deciding on restaurant brands as well as the sculptures that will adorn the entranceway and the art that will hang throughout the hotel, she said.

A considerable amount of effort and money have gone into the common areas, including the bars, restaurants, spas and gathering places. Indeed, engineering challenges in these areas contributed to project delays even before the pandemic hit. The final cost of the project will be at least $200 million more than the original budget.

On the third floor, for example, one new feature of the renovation is an 8,500-square-foot grand ballroom that sits directly below a 70-foot lap pool and wooden deck on the fifth floor terrace. Supporting the weight of the pool and preserving the 18-foot ceilings on the third floor meant putting in huge, 60-foot steel beams above the ballroom.

All that work was to ensure that the common spaces maximize the property’s key asset: spectacular views of the Mississippi and panoramic cityscapes.

Similarly, the restaurant on the fifth floor will offer the same vistas and opens onto the outdoor pool where there will be a bar and seating for about 80 people. Also on the terrace, several air-conditioned private cabanas will feature their own small bars and televisions.

“They will be the second-best place in town to watch Saints games,” Carow said.

Riding up the construction elevators to the top of the building, another notable — and expensive — feature of the project was the addition of a walk-up 34th level in order to allow for an open air observation deck.

Just below, the 33rd floor is the old revolving space remembered by some New Orleanians as the Top of the Mart, a cocktail lounge inspired by the World Trade Center’s original name. For many years, it served as the Plimsoll Club, a dining and event space that moved to the Westin New Orleans in 2010.

It will no longer rotate, but will still offer panoramic views from more than 400 feet up for cocktail receptions, dinners and the like.

In the 341 hotel rooms below, the tons of Italian marble have already been fitted and Jackie Santos of Bill Rooney Studio is making the final interior design choices. Her style for the Four Seasons at One Dalton Street in Boston offers a clue of what the finished New Orleans hotel will look like: curated art collections with a local flavor, New England vintage quilts, “polished mahogany and jet mist stone.”

Carow is working with a small management team of five now, but said she’ll begin hiring in earnest by January.

“Look for a lot more communication about hiring after the holidays,” she said. “I think we’ll ramp up to 500 by the end of next year as business recovers. I think that will be done pretty quickly.”