Edward Durell Stone was one of the most contradictory architects of the 20th Century. At the height of his career in the mid-1960s, he was the Frank Gehry of his day, wildly popular designing buildings all over the world. But his modernist formalism was often dismissed by the architectural elite, for whom he was a monger of kitsch.

A southerner by birth, Stone’s one major building in his native region was the International Trade Mart in New Orleans, completed in 1968 (it would later become the World Trade Center). In a testament to the adaptability of the architect’s work, the once-shuttered building is being transformed into a Four Seasons hotel and luxury high-rise residences.

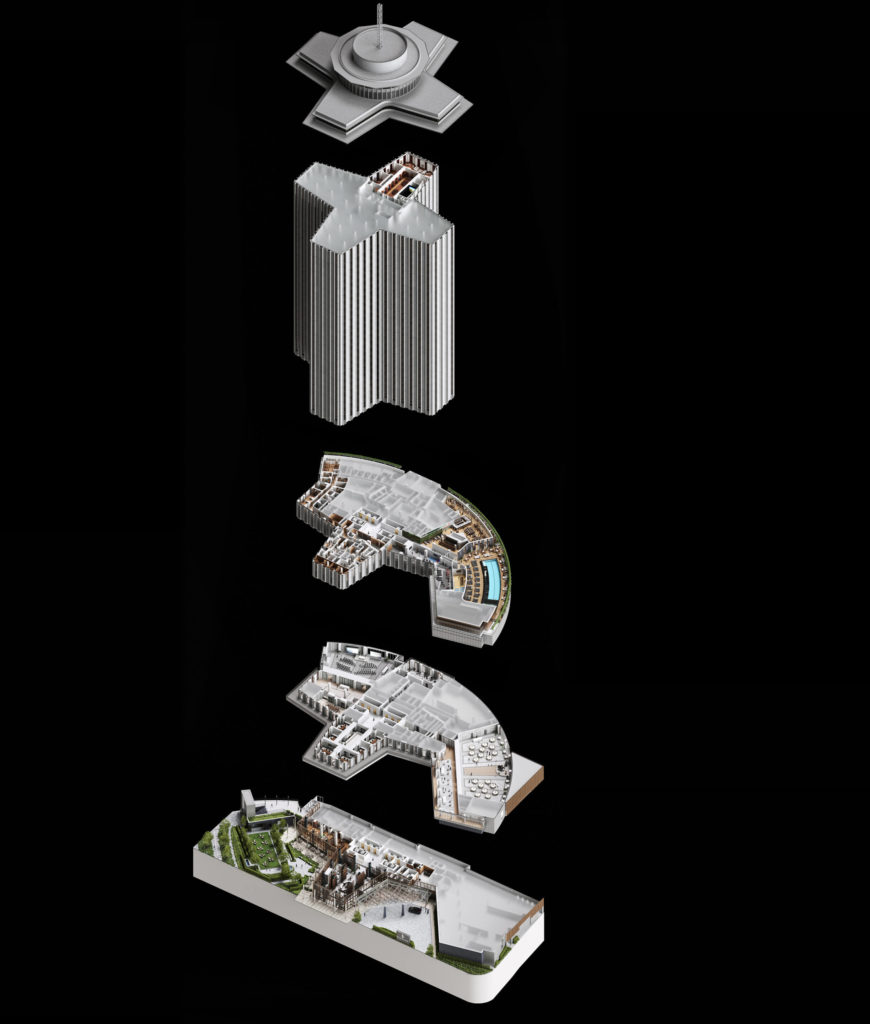

Stone’s landmark is a cruciform design whose four wings are aligned with the points on the compass, a powerful metaphor for an international trade building. But these tapered wings are proving themselves highly adaptable.

“It’s such a 1960s building. It has all of the exuberance of the decade,” said Gary Johnson, principal and president of CambridgeSeven Associates and architect of the building’s transformation. “It was a time of wonder and excitement and renewal.”

“These wings lend themselves better to hotel and luxury residential use than to an office building,” Johnson continued. “The elevators are at the very core and the corridor walk to your room or apartment is very short.”

The building has an enviable location in the Crescent City, right at the foot of Canal Street and overlooking a small circular park, the Spanish Plaza, fronting directly on the Mississippi River. Given its prominence on the skyline, who would renovate and repurpose the building was decided by a competition held by the city with guidance from the National Park Service and the Division of Historic Preservation for the state of Louisiana. The tower is on the National Register of Historic Places.

A big architectural move is at the base of the tower, which is a curved podium from which the skyscraper ascends. This structure contains amenities like ballrooms, restaurants, and a pool. At the opposite end, the circular crown on the building will become a historical installation called VUE Orleans, which will track the city’s fascinating history under multiple flags, including the French and the Spanish.

“There will be 15,000 square feet of historical exhibition on level 2, and then you take an elevator to the circular crown, which will have stunning views of the river and the skyline,” Johnson explained.

Alan Leventhal is a Boston-based real estate executive who has a personal financial stake in the project. His wife is a native New Orleanian and he admits to a deep affinity for the city.

“A few years ago, I saw the International Trade Mart and said to myself, ‘That would make a great hotel,’” Leventhal said. “We pulled together a team and got excited about the competition the city was having to redevelop the complex.” (Leventhal’s stake is unrelated to his Boston-based firm, Beacon Capital Partners, of which he is founder and CEO.) He challenged naysayers who said New Orleans could not support this level of high-rise residential luxury.

“We’ve already proven there’s a market,” Leventhal explained. “What we had projected our sales and apartment prices would be has been exceeded by the market. The demand is both local and national. We have buyers from other parts of Louisiana and Texas and California. New Orleans is the kind of city where if you have a connection to it, it pulls you back.” Other members of the project team include Carpenter & Company as investors, Bill Rooney Studio as interior designers and Woodward Construction, according to the building website.

“This is the largest private development in New Orleans history,” Leventhal continued. “I’ve told the team that you’ll never be in another project that has more impact on a city.”

A local scholar of modernist architecture, John P. Klingman, praised the renovation project, but with some reservations. “While at the time I refused to champion the building’s preservation, it’s a renovation project that has been well done,” said Klingman, professor emeritus of architecture at Tulane University. “There are not a lot of other New Orleans buildings you can point to as being quintessentially mid-century. Its renovation and preservation are really good news.” Even so, Klingman added that Stone’s “brand has held up better than his architecture.”

For a city in which social standing is everything, the Four Seasons Hotel, scheduled to open in July, promises to be the ultimate venue for weddings and other events. Indeed, the building has come a long way since its post-Hurricane Katrina condition, Johnson said. It was damaged by the storm and stood fallow from 2011 until construction began, and under the threat of demolition.

“It was sad to see that part of the city so forlorn. The building was derelict. It was an iconic ruin.”