The Architect’s Mentor Series – 09 Ann Cline

Of the many and various ways to describe Ann Cline, heroic is least likely, though she is a hero of mine and the many she taught. Ann Cline was one of my first architecture teachers at Miami University and interested in the so-called primitive hut as the most crystalline way of comprehending, practicing, and sharing architecture. Only years later have I appreciated how influential her thinking has been in my daily practice.

Her vision of hut building and dwelling was a broad but personal one. For Ann, very small structures, often self-built and outside the establishment, have the capacity to explore and convey large ideas about the fundamental purpose of buildings; that is to make space for simple but essential rituals of ranging from individual contemplation to intimate conversation among a few to a shared experience among the many.

As a teacher, she could effortlessly move between historical references whether Lao Tzu’s philosophy of retreat or Saint Anthony’s spiritual seclusion, but also see the correspondence of older ideas to own times and concerns like exploring poverty and necessity in James Agee’s sharecropper cottages, productive nostalgia in the Puerto Rican casitas of the Bronx, musical culture-creation in blues juke-joints, even the fumbling attempts of star-architect’s follies attempts to express a truth about ordinary life in built form. These eclectic spaces all have something to say about any mode of practice that is essential, honest, and intended as much for others as for one’s self.

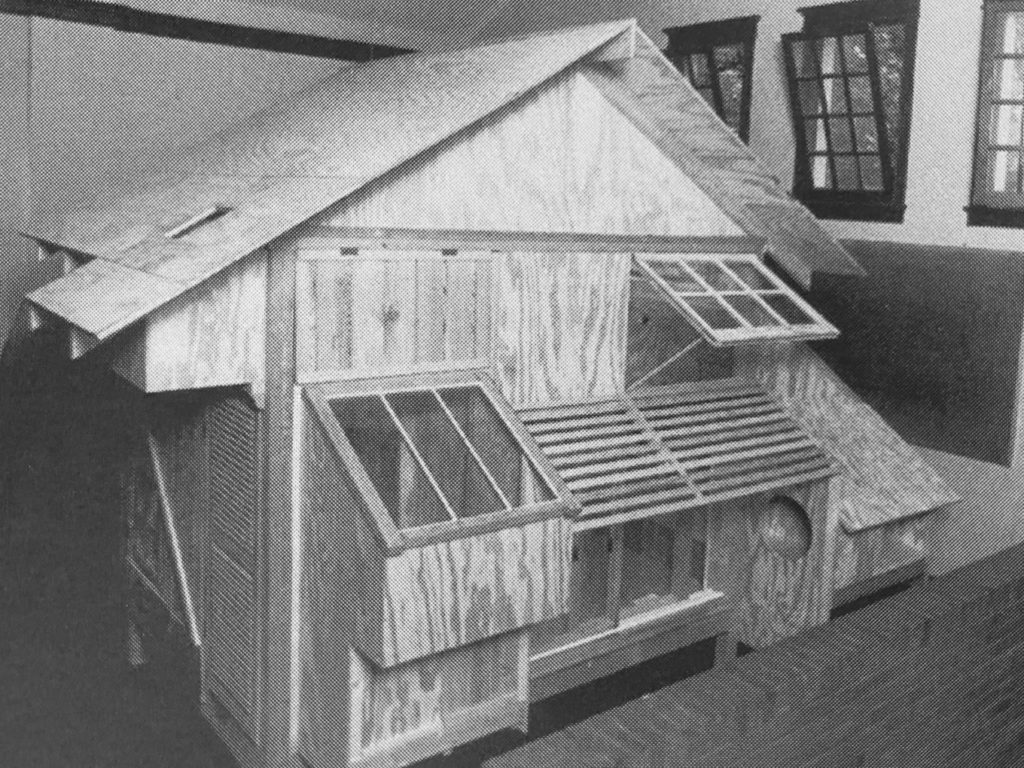

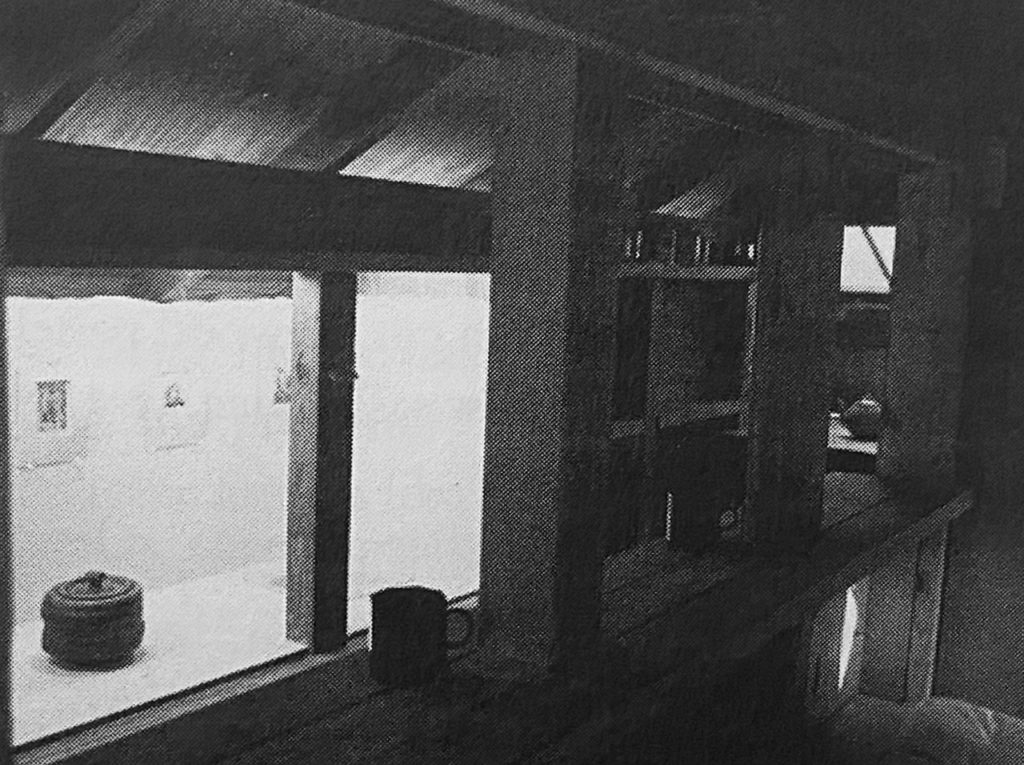

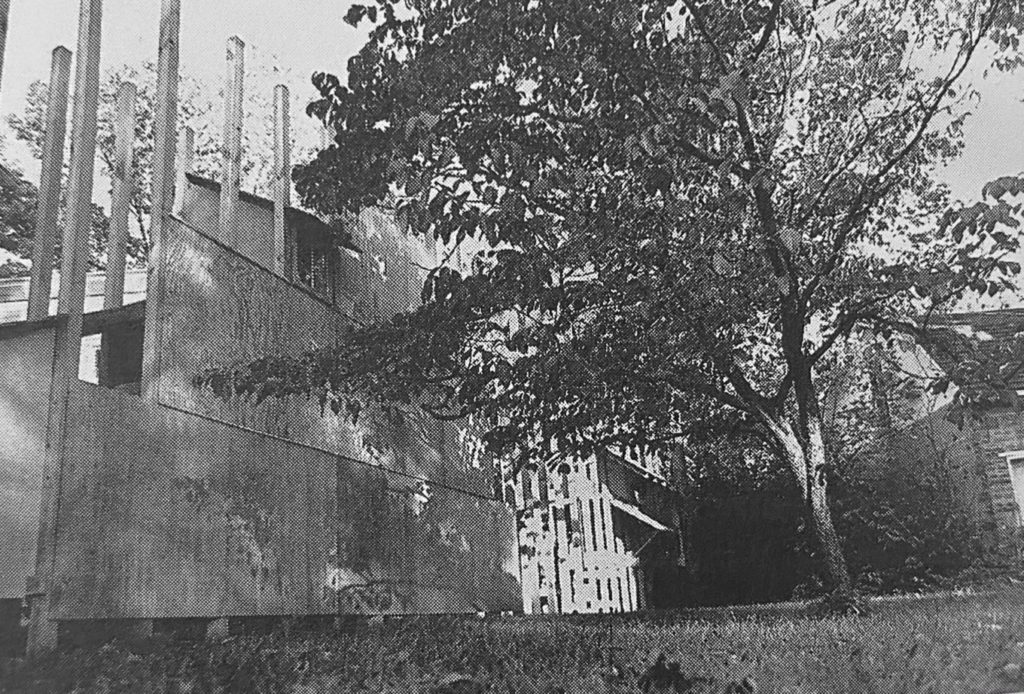

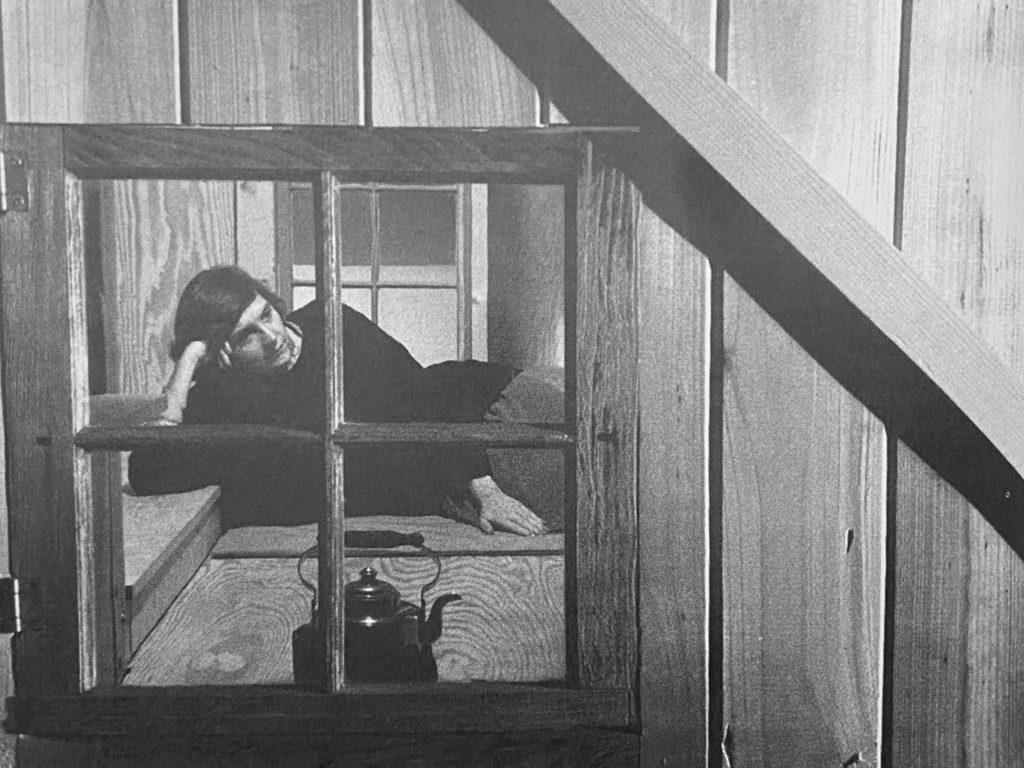

One of her greatest insights was that she saw architecture as space to be shared. The making of an object was one thing, but the ongoing life of the mind, of a club, a friendship, a chance meeting of strangers, these performances and inhabitations were the reason for architecture in its widest expressions. Being an expert in the Japanese tea ceremony, she saw the ancient discipline as a template for a modern ritual and a reason for the structures that to enable it. She decided to build her own tiny tea house in the backyard and out of plywood scraps and castaway windows from the local hardware store. These little, noble, ragged structures, holding no more than several people did indeed host proper tea ceremonies but also informally serious art exhibitions, dramas, and poetry readings and space for individual rest, enjoyment and thought. The teahouse became a common point of reference for the community, even recreating a version inside the architecture department’s lobby.

Before I said goodbye to my undergraduate experience, I visited Ann to pick up a copy of her book “A Hut of One’s Own”. She invited me also to visit her tea house. While I sat there alone, in a slightly cramped but engaging silence, I experienced the value of such modestly ambitious spaces where high and low thoughts freely mixed. Afterward, in typically excellent humor, she jokingly asked if someone as tall as me could even have a contemplative experience under such a low roof. Of course, stuffing myself into a container about the size of a chicken coop for a meditative moment provided laughs with her and ongoing grist for thoughts about buildings with others. It was the last time I had the privilege of speaking with Ann.

Though she died a couple of years later, her mentorship has continued to persist and grow. In my professional life, I have had the opportunity to design ever-smaller structures, shelters, cabanas, benches, kiosks, bunk beds, pylons all aiming to keep up with her richness of thought where architectural practice is generous, that is, able to make as well as to give.