The Sustainable Aquarium: Less is More

How aquariums are making their conservation and sustainability actions the theme of exhibits and vital components of their architecture.

View Post

“The edge of the sea is a strange and beautiful place.” –Rachel Carson, The Edge of the Sea

Waterfronts are ecologically vital opportunities for bio-positive design. Meaningful steps are being taken to steward, protect, and reinforce some of the most obviously productive ecosystems such as forests and wetlands; however, we also must act on opportunities at seemingly marginal areas such as the edge of the sea.

At first glance, the tidal zone appears to be a barren expanse of sand or rock. Indeed, the ocean’s edge is a tough place to live, seemingly fit for a limited group of creatures that can survive in breaking waves that strike with the force of two tons per square foot, constantly advancing and receding tides, and the harsh extremes of the land world where plants and animals are exposed to heat and cold, wind, rain, and drying sun. Yet among these seemingly desolate stretches of rock or sand are an impressive array of plants and animals that are critical to both marine and terrestrial food webs.

Between the equator and 30 degrees latitude are the especially fecund coastal ecosystems of mangrove swamps and coral reefs. At higher latitudes, coasts that are not estuarine are typically either sandy or rocky. And just as Cape Cod forms a rough zoological boundary between the warm southern waters of the Gulf Stream and cold northern waters, New England’s coast is a transitional zone with both sandy beaches, like those to the south, and rocky shores like those to the north. As a result, the hard edges of our wharves and harborwalks provide opportunities to support flora and fauna that are native to the rocky edges of New England.

It’s worth noting here that, even in 1955 when Carson wrote The Edge of the Sea, scientists understood that ecological boundaries were creeping steadily north:

Curious changes have been taking place, with many animals invading this cold-temperate zone from the south and pushing up through Maine and even into Canada. This new distribution is, of course, related to the widespread change of climate that seems to have set in about the beginning of the century and is now well recognized – a general warming-up noticed first in arctic regions, then in subarctic, and now in the temperate areas of northern states.

While the current rate of change will likely be exceptionally harmful, any bio-positive design at the water’s edge must acknowledge that the shore is a place that is forever changing – between phases of the moon, through seasons, years, and geological eras. Opportunities for design at urban edges start with an understanding of marine and ecological flows and functions.

Marine bio-positive design starts by studying the flora and fauna that existed at the site before human interventions, acknowledges the need to reinforce life that remains (or eradicate invasive species), then uses this research to inform the design of built objects to facilitate the natural activities that could occur at the site. An exceptional recent example is Seattle’s new seawall, engineered by Parsons, which supports restoration of the chinook salmon populations that swim through Elliott Bay on their way to the Duwamish River and other waterways. The seawall design includes translucent sidewalk panels in the overhanging walkway above to allow for sunlight and plant growth below; a textured surface to the wall promoting algae growth that provides food for salmon; and “rock mattresses” at the bottom providing homes and hiding places for marine organisms.

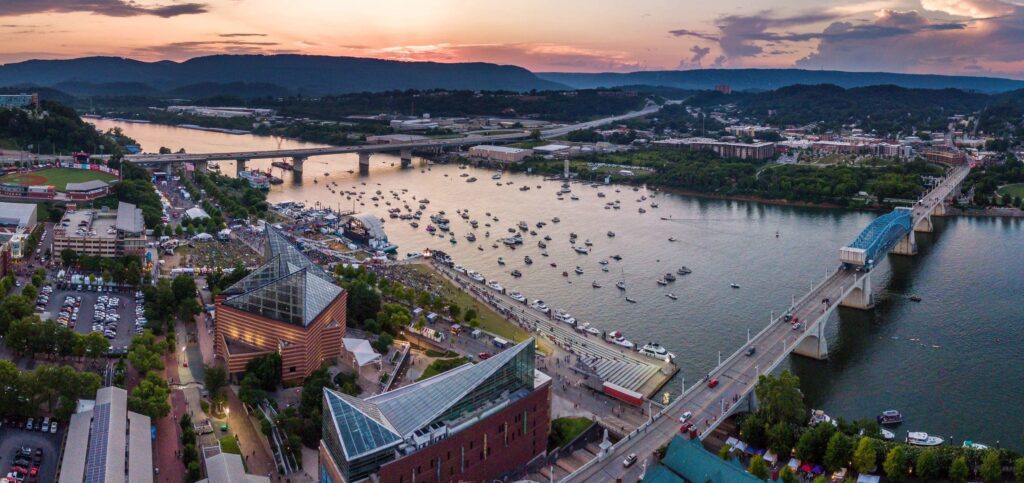

At CambridgeSeven, we’re working with clients to design waterfront sites that reinforce their coastal ecologies while also making these sites more resilient and educational. As part of our comprehensive campus plan for the New England Aquarium, we’re re-imagining Central Wharf and the Harborwalk to improve resiliency; while at the Roux Institute at Northeastern University, in Portland, ME, we’re addressing resiliency and restoring the coastal edge along the shore of Casco Bay. Following is our list of strategies for designing harbor edges for sea life:

Finally, we should celebrate – through views to and from sea walls, harborfront interpretive graphics, and controlled opportunities to access the water – the abundance of life at the edge of the sea. If we welcome and highlight the plants and animals living next to and around our waterfront architecture, we can create a new generation of advocates for restoring our marine ecosystems.

All too often, people think of the shore as desolate stretches of sand or piles of rocks; our urban waterfront architecture too often neglects the moment when water meets land. However, this zone is a critical link between terrestrial and marine life and a “strange and beautiful place” for which we at CambridgeSeven are collaborating with clients to create designs for a range of waterfront conditions – from Gloucester’s Harborwalk to granite wharves at the New England Aquarium to a beach-front lab on Virginia Key in Florida – each inspired by the sites’ specific ecological needs and unique place at the edge of our world.

How aquariums are making their conservation and sustainability actions the theme of exhibits and vital components of their architecture.

View PostThe way that we build can have profound impact on our oceans and, in an era in which global warming is rapidly changing ecosystems, building responsibly is vital for our oceans.

View Post